May 28, 2022

Written by: Chelsey Simoni, RN, MSN

“We can’t stop the waves, but we can learn how to surf.”

It is always a refreshing experience when an unprovoked meeting of the minds transpires. To be present with some of the most outstanding modern-day scholars thoughtfully inciting meaningful discussion, fueling reflection, and motivating more profound thought than the predictable, dull conversation.

The HunterSeven team was introduced to Dr. Kate Hendricks Thomas, Ph.D., in the summer of 2021 after a mutual friend shared that the former Marine Officer had been actively battling breast cancer. As a team of fellow scholars of medical and social disciplines, we reached out to Dr. Kate – first and foremost, to offer our support and assistance. Secondly, to share intellectual insight.

In 2017, years before meeting Dr. Kate via Zoom Video chat, I had taken an undergraduate class involved with Public Health Perspectives, addressing barriers to care in mental health, which was theoretical but required an abundance of academic writing. Rummaging through pages of literature in hopes of finding a trustworthy source, I stumbled across a series of papers published by two female Marine Corps veterans, Kate Hendricks Thomas and Sarah Plummer Taylor. I began reading into the pair iterations on mindfulness interventions in the training environments to improve resiliency in military and veteran communities titled “Bulletproofing the Psyche” to grab some facts surrounding veteran mental health.

What happened next, I did not expect.

Veteran suicide is at an all-time high and continues to rise despite hailing efforts to curb this pandemic. “Within the military community, much of the issue lies neither in lack of screening for depressive disorders nor in the medical care available to service members suffering from depression. Rather, the challenge is getting veterans to avail themselves of treatment services….” Dr. Kate wrote.

I sat back in my seat and mumbled how most providers couldn’t relate, and going through those painstaking motions was more anxiety-provoking than the emotional, morally injurious burden itself.

Questioning whether or not these Marine Corps officers had truly experienced this or were they the direct-medical-commission type pushing the mental health agenda for the “greater good,” I read on.

“Part of the issue is the stated disconnect combat veterans feel from civilians, even civilian mental health professionals who treat the military population. Service members and veterans often feel they are wasting their time dealing with people who cannot relate to their perspective, and many feel more comfortable in the war zone….”

Abruptly retracting my previous thought, I continued to read, inadvertently biting the side of my thumbnail as Kate and Sarah had personally singled out my arrogance.

Studies show that many of those who enlist or choose to serve in the military grow up in less-than-perfect homes with disruptive childhood events and broken families—those who choose the path of service hoist up that bulletproof armor to protect themselves from vulnerability. Most of us are guilty of this and buy into the warrior culture that vulnerability is weakness. I lived by this ethos my entire life by compartmentalizing and avoiding unsavory concerns as a coping mechanism for survival. But the exact opposite is true – vulnerability is critical to healing and survival, as Dr. Kate wrote. Of course, this is easier said than done.

Fast forward a few years.

What Dr. Kate wrote in that article, published in the Advances in Social Work (2015) on the bottom half of page 315 titled “Protocols,” had changed my entire outlook on mental health resilience. I intensely argue any diagnosis I was given surrounding post-traumatic stress for reasons I cannot explain. But this concept of “stress injury” discussed by Dr. Kate and Sarah made a lot of sense.

Moral injury, stress reaction, fight or flight impulsiveness. Everything started to make sense in ways I could personally understand. I felt invisible from providing medical care for suicides, both attempted and successful, to a painfully dark transition back into the civilian world, to nursing school and practicing medicine in level one trauma centers.

For our fellow females who wore the uniform, I highly recommend listening to Dr. Kates’s twelve-minute TEDx Talk linked above titled “Invisible Veterans.” You’ll laugh when she talks about intensity and relate when she mentions that she knew how to press the gas but didn’t know where the brake was.

Today, the key to my success was this one acknowledgment:

Vulnerability supports the recovery of moral and stress-related injuries.

I kept up with Dr. Kates’s academic works, setting alerts to my email when she published through ResearchGate and grabbing copies of her books when they were released. Her valuable work in the veteran space slowed in recent years. And it wasn’t until July of last year that I found out why.

Dr. Kate served as a United States Marine from 2002 to 2012. She held various billets, from training environments to senior leadership. Deploying to Iraq’s Camp Fallujah in 2005, Kate would often run convoys through the notorious “Triangle of Death,” an area of operations notorious for IED-packed supply routes and side streets laden with vehicles stuffed with explosives awaiting American convoys. An environment that made even the toughest warfighters cringe.

Being a female Marine Officer in 2005, Kate was scrutinized based on her gender (which she openly discusses) and would do whatever she could to meet and exceed standards set to leave no room for skeptics. During her little downtime, she would run the base perimeter closer to the center to avoid the daily mortar attacks and pop-shots. Her safety concern was in the combat-related attacks, not so much for the burn pits, airborne particulates with embedded heavy metals, and chemicals she would be unknowingly exposed to at war. Most of us don’t consider the long-term medical impacts, focusing on war’s immediate, life-threatening dangers.

Leaving the Marine Corps and taking note of the systemic changes necessary for military personnel and veterans transitioning from service, she earned her doctoral degree in health education and promotion. She married, began a family, and published her first book, “Brave, Strong, True” in 2015. Her life was exactly what she wanted it to be; she was researching, teaching, writing, publishing – she was helping those who didn’t even know they needed it.

Until September 2016, the Department of Defense released a Periodic Environmental Monitoring Summary from Camp Fallujah and the surrounding vicinity, discussing the deployment-related health risks associated with service in Fallujah between 2004 to 2011. One of the main concerns was limiting exercise and strenuous movements to prevent exposure to airborne particulate hazards. The DoD posted a memo 11 years after Kate left Iraq.

The 38-year-old, healthy mother went to a routine appointment at her local Veterans Affairs hospital two years later. It was there that her nurse practitioner recommended she be further examined based on her service in Iraq. Despite being without symptoms, Dr. Kate was ordered to have a mammogram – uncommon for someone under 40 years old with no familial history of genetic predisposition.

That January (2018), Kate received word that she had been diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer.

She was diagnosed with not just one but three types of breast cancer.

It had metastasized and spread from head to toe.

Just thirty-eight years old and diagnosed with terminal cancer. Kate said what was more disturbing than her diagnosis was how prevalent cancer was among her fellow female veterans. She crossed paths with the only other females from her deployment to Iraq and found out they had the same type of cancer.

2021: Enter HunterSeven Foundation

Our mission at HunterSeven Foundation, much like Dr. Kate’s, is to use our lived experiences to identify evidence-based tools in our toolbox to promote health while providing this priority population with preventive strategies in early-stage settings enacting overall resilience.

I reached out to Dr. Kate in July of 2021; we chatted numerous times about health and wellness, prevention, and public health while she was actively involved in treatment. I explained the purpose of our mission encircled in the principles of public health, to which she agreed, but what I remember most was her smile. She had a brilliant, calming smile.

Weeks ago, Kate was placed in hospice (end of life) care.

When I read this, my heart sank, and I immediately offered any support I could give. Dr. Kate passed away from breast cancer on Tuesday, the 5th, surrounded by her loved ones, peacefully at 42-years old.

Kate left this world with many life (saving) lessons.

It is impossible to highlight them all, but her work in cancer prevention before her untimely death is one lifesaving legacy. The MAMMO Act (Making Advances in Mammography and Medical Options for Veterans Act) and the Dr. Kate Hendricks Thomas SERVICE Act (Dr. Kate Hendricks Thomas Supporting Expanded Review for Veterans in Combat Environments Act) have both passed the Senate unanimously in support of prevention, early identification, and screening, Dr. Kate will continue impacting many female veterans lives for decades to come.

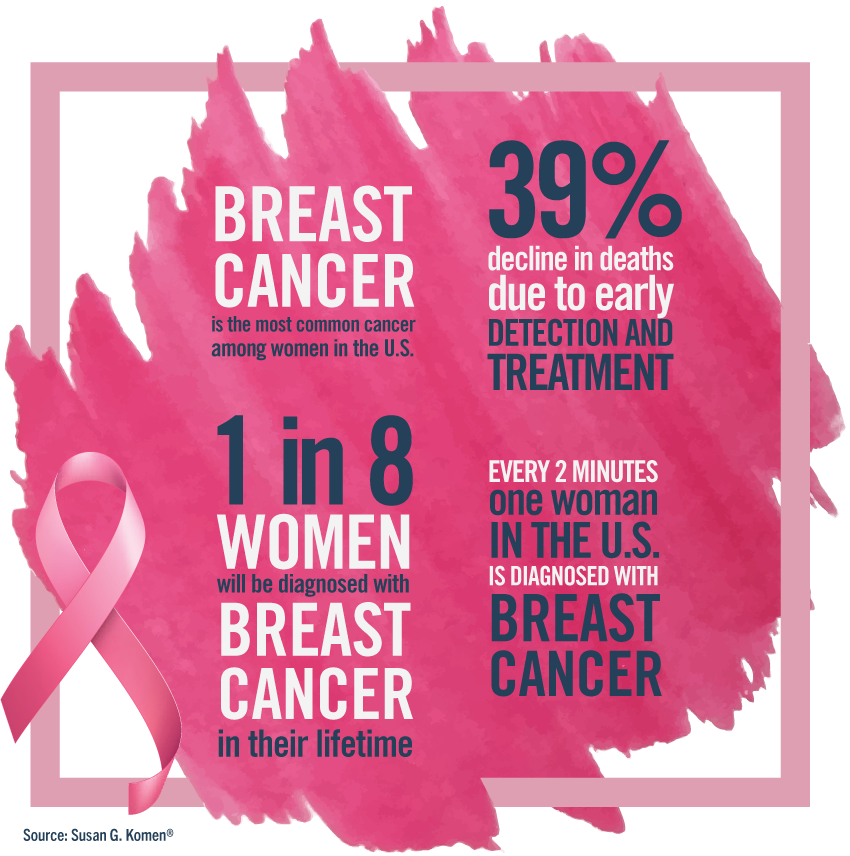

Women veterans are drastically under-represented in the Post-9/11 era, ranging from 7% of the Marine Corps up to 17% across the Department of Defense. Interestingly, despite being less represented in service, female-related cancers are the most frequently occurring cancers during active duty between 2001 and 2021.

Last summer, we sat with Kate and discussed the prevalence and incidence rates of breast cancer in post-9/11 female veterans. We took the civilian incidence rates for breast cancer diagnoses in 2010 (year chosen at random) and compared them to the number of female service members diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010.

At face value, the raw numbers weren’t shocking.

Seven hundred twenty new breast cancer cases were diagnosed in 2010 across the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

2010 – Civilian Females (ages 18-44) in the United States breast cancer incidence rate:

21 per 100,000

2010 – Military Females (ages 18-44) on active-duty breast cancer incidence rate:

354 per 100,000

Suppose you are a female who served on active duty post-9/11. In that case, you are approximately 34x – THIRTY-FOUR TIMES more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer when compared to non-military, civilian females of the same age range. We created a custom cancer screening chart based on exposure risks for post-9/11 veterans that you can find here. Understand your exposures, and get checked.

We wouldn’t have known about these numbers if it weren’t for Dr. Kate and her heroic, outspoken battle. But Kate was more than breast cancer; she was more than toxic exposures. She was the insightful empathetic leader we all needed and her memory should be honored in such a way that expands on her compassionate way of life and leadership.

Thank you, Dr. Kate.