A combination of military-related stressors, lack of sleep, and how your body becomes its own worst enemy.

January 12, 2023

When you ask someone what “inflammation” means, they’ll respond that it is the result of an acute (short-term) injury or illness that assists in the healing healing process, and acts as a temporary protective mechanism to the cells and tissues surrounding the injured site.

At face value, inflammation is a good thing.

But what if we looked at inflammation by occupation? Or duration?

We’ve seen professional athletes injured on the field and other high-intensity occupations like firefighters, police officers, and other first responders face similar injuries in their day-to-day jobs. Most of the time, those injured in the line of duty are pulled aside to recover within minutes-to-hours of the injury occurring. Of course, this isn’t always the case. With our forward-deployed military personnel being a unique group subjected to acute injury, subsequent inflammation, and inadequate recovery times.

It is essential to ask the question: What are the long-term implications of military occupational roles and the extent of immune changes after operational injuries and exposures causing systemic and chronic inflammation?

It sounds overwhelming, so we’ll make it more digestible to drive home the importance of adequate recovery.

Our service members face unique physiological challenges both stateside and overseas, including physically demanding tasks, encapsulating combat environments (inside small buildings, vehicles, protective gear), extreme weather, temperatures, and ecological factors like blinding sandstorms as well as life-threatening, dangerous situations that enact the bodies’ fight-or-flight mechanism.

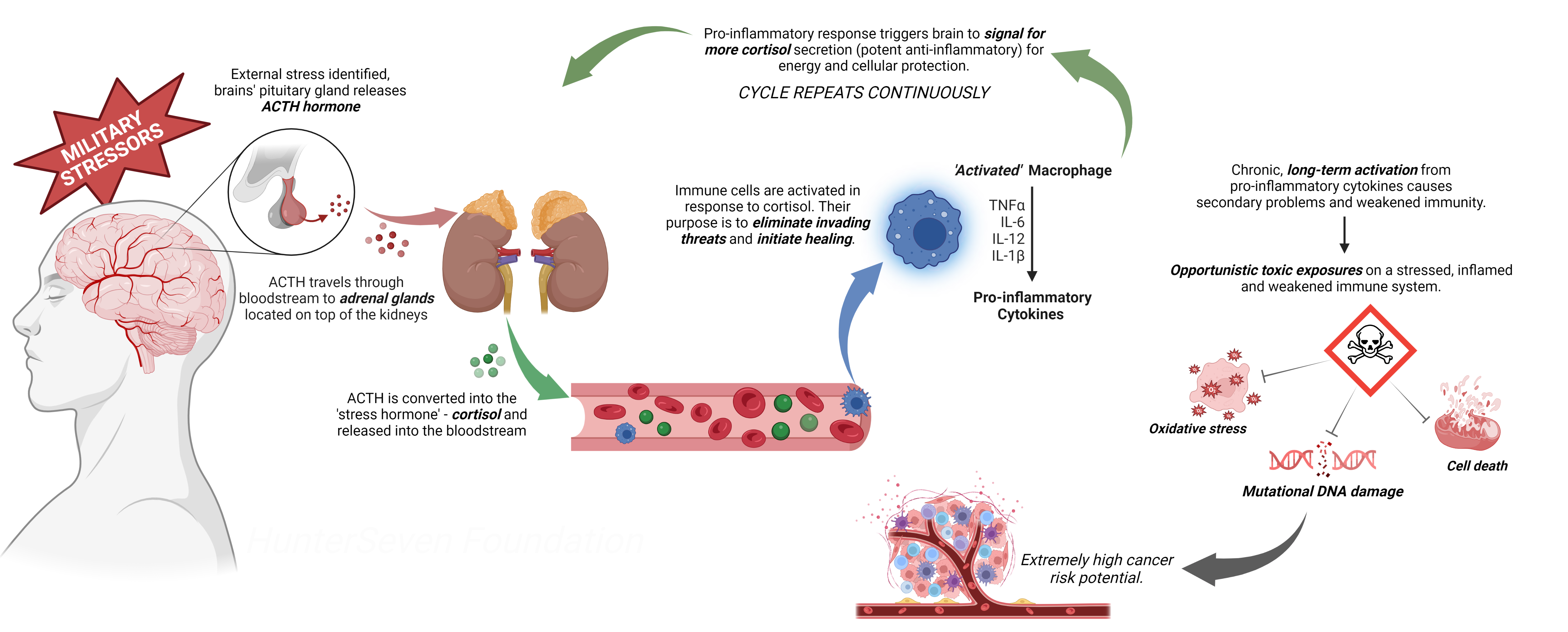

When combining those events, the body’s heart rate increases (the physical reaction of the fight-or-flight response), the core temperature increases (increased sweat to cool the body through the skin’s dermis), and your inflammatory biomarkers increase.

What is an “inflammatory biomarker”?

From a military perspective, when the body detects something wrong or senses a foreign invader or enemy, it sends inflammatory “shadow gunships” to the front lines, such as white blood cells, cytokines, and acute-phase proteins. Once the inflammatory “shadow gunships” remove the foreign invader or “enemy,” they return to “base” to refuel, reload, and replenish their supplies, so they are ready and rested until they are needed again. It is a normal physiological reaction that is required for survival.

But what happens if we have repeated, long-term stressful experiences or “combat engagements” without allowing our “shadow gunships” to resupply? The gunship depletes its main weapons systems, begins running out of fuel, and the foreign invader enemy overruns the troops on the ground. The gunship becomes more of a liability than an asset.

The same goes for any “quick reaction force” (QRF). They are mission-ready for short-term (acute) engagements, not long-term (chronic) sustainability. That is the best way to think of your body’s inflammation system.

Repeated stressful experiences and exposures without having time to return to “base” or back to normal, “resupply,” and recover between episodes or engagements lead to chronic, systemic (whole-body) inflammation.

Many of the biomarkers we use in healthcare fall under the “inflammation” umbrella but have specific and unique purposes, and vary in time, duration, and health outcomes. There are dozens of inflammatory and related biomarkers, but some of our favorites we prefer in practice are the pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune-related effectors, and acute-phase proteins below:

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6),

- Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β),

- Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-a),

- Complete White blood cell count (WBC),

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation rate (ESR),

- Platelet / Lymphocyte ratio (PLR),

- C-reactive Protein (CRP),

- Immunoglobulin-E (IgE),

- Immunoglobulin-M (IgM),

So why exactly is chronic, long-term inflammation dangerous to your health?

Two pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-6 can communicate with the central nervous system (CNS) as they pass freely through the blood-brain barrier but can also activate “afferent” neurons (nerve fibers that relay external sensory information into specific regions of the brain which force the brain to react). While this may be good for short-term reaction and fight-or-flight-like abilities, it wreaks havoc long-term.

Elevated levels of these cytokines can stimulate “sickness” behaviors with specific responses, including weight loss, depression, fatigue, headaches, heavy sweating, and sleep disturbances. These are all things our post-9/11 military members and veterans face overseas and post-deployment. However, as noted in our retrospective study on Iraq War veterans, these individuals rarely had these symptoms before deployment. More so, those with elevated levels of IL-6 are six times more likely to experience symptoms of ill health and three times as likely to experience a significant cardiac event.

It is also important to note that when those pro-inflammatory cytokines increase, the body’s humoral immunoglobulins (series of serum proteins that function as antibodies) build-up and release in response to the inflammation. The most relevant is “IgE”. IgE is the antibody responsible for allergic reactions and the pathology of allergies themselves. Notoriously, exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) like those in diesel and jet propellant fuels (absorption exposure) and fumes (inhalation exposure) have been shown to increase IgE levels in the blood significantly. Increased levels of IgE in the body can also explain why so many post-9/11 military veterans return home from air-polluted environments with increased sinusitis, rhinitis, and asthma, as well as other IgE-mediated conditions like dermatitis, eczema, and skin-related conditions. And not to forget the massive uptick in hormone dysfunction and autoimmune diseases due to unknown causes.

Most importantly, these “protective measures” can, and will fail. Systemic cytokine concentrations and, as a result, chronic inflammation have been associated with both increased cancer risk and cancer progression by suppressing fatigued immunity, suggesting an essential link in military-veteran tumorigenesis, carcinogenesis, and prevention.

So, how can one decrease stress and inflammation?

- Sleep is one of the most important aspects of stress management. Quality sleep is the origin and foundation to our every day lives and long-term health. Without sleep, our progress physically and physiologically become compromised and we lack the energy to properly function and sustain our daily activities. Read more about sleep habits and good technique on our fact sheet available here. For those who currently ‘overdose’ on melatonin, we highly suggest checking out Bravo Actual Supplements sleep aid, Rack Out. A few years ago, our veteran medical team at HunterSeven Foundation sat down with the chemical genius’ at Bravo Actual to create a sustainable, non-addicting, evidence-based sleep aid to focus on natural sleep patterns through decreased inflammation, neurotransmitter modulation, natural cortisol reduction and vasodilation. We stand by it, not just that you’ll get a good nights rest, but within one month you’ll feel a difference in both your sleep and daily activities.

- Diet is critical in inflammation and stress control. While serving we eat carbohydrate-heavy foods, such as protein bars and meals-ready-to-eat (MRE) while on-the-go, combined with carbonated energy drinks with artificial sweetener to get us through the day. This is no longer sustainable. Nothing boosts inflammation and enacts the stress reaction more so than inflammatory foods. For a full, in-depth review we recommend checking out Dr. Gabrielle Lyon – she offers excellent insight on her podcast and social media accounts. In the mean time, here are some to avoid:

- Refined carbohydrates (white bread, pastries, pasta)

- Fried foods (French fries, fried/battered meats)

- Soda, and sugary drinks (orange juice included)

- Margarine (Real butter only)

- Sugar-heavy foods (desserts, etc.)

- Exercise – more specifically, Yoga. Yoga is the most underrated activity for health and well-being. Yoga can help reduce stress because it promotes relaxation through regulation of the nervous system and passively allows time for self-reflection. Yoga can benefit three aspects of ourselves that are often affected by stress: our body, mind, and breathing. Check out what fellow Army veteran, Phil Sussman and his medical Provider brother, Mike Sussman are doing through American Yogi. What is unique about American Yogi is that co-owner, Phil, has experienced combat-related injuries and witnessed unforgiving trauma, what we deal with through stress and inflammation is a lived experience for him as well. Give it a shot, you won’t regret it.

LEARN MORE ABOUT STRESS IN OUR DOWNLOADABLE HANDOUT