Abigail DePaulo should have been celebrating her fourth wedding anniversary alongside her husband, Carmen, on March 1st. Instead, she spent March 6th, the two-year mark of his untimely passing, by his grave in Arlington National Cemetery with their two little girls.

SFC Carmen Joseph DePaulo III, known as “CJ,” enlisted into the Army in his mid-twenties. He began his short-lived career in the 25th Infantry Division based in Hawaii before attending the Special Forces Assessment and Selection course in April 2013. By December 2014, CJ had earned the coveted “Green beret” and would become the special forces medic of ODA 3314, a detachment within the 3rd Special Forces Group. CJs first deployed to Chad in 2016, a landlocked country in central Africa. Shortly after returning home to Fort Bragg, he met Abigail. The two hit it off instantly and were inseparable. While dating, CJ would deploy twice more to Africa – Arlit, Niger in 2017 and 2018.

Both times he deployed he returned to Abigail, unscathed.

Following his last deployment, CJ began having bouts of diarrhea and would have an undeniable urge to use the bathroom shortly after eating meals; his stomach didn’t “feel right.” At first look, a 33-year-old with no family history of colon cancer and unspecific stomach issues wouldn’t have raised a red flag or suspicion for any medical provider.

CJ heard the routine responses: “eat more fiber” and “it is probably stress-induced irritable bowel syndrome or hemorrhoids,” when he mentioned the blood in his stool. But CJ and Abigail knew it was more serious; they felt something wasn’t right and pushed for an appointment at Womack Army Medical Center with a gastroenterologist. It took eight months for CJ to be seen. To add insult to injury, during that appointment, the provider did a glance before moving his focus to his computer; not once did he physically examine CJ.

CJ and Abigail pushed for a colonoscopy; the soonest they were told he could be seen was ten weeks away. The young couple went home and anxiously awaited the appointment. Abigail watched as CJs pain worsened, and he began to lose weight rapidly. His condition was quickly declining, and some nights, he would sweat so bad the bed sheets would become drenched. They began contacting off-post medical facilities in hopes of getting a colonoscopy sooner. Luckily, he was seen within a few weeks at the end of August but was challenged with grim results; their once-silenced concerns quickly became reality.

On September 11th, 2019, the day after his 34th birthday, CJ was diagnosed with late-stage III colon cancer.

The diagnosis didn’t make sense; CJ had no usual risk factors, and he was a young, fit, healthy Green Beret. Despite an occasional glass of whiskey, a cigar, and a mild smoking habit, he had no family history. He didn’t deploy to Iraq or Afghanistan and hadn’t been surrounded by the infamous “burn pits” – he had deployed within Africa; to nations not commonly thought of concerning toxic exposures. While we thought CJs situation was a rare, one-off case. We were wrong.

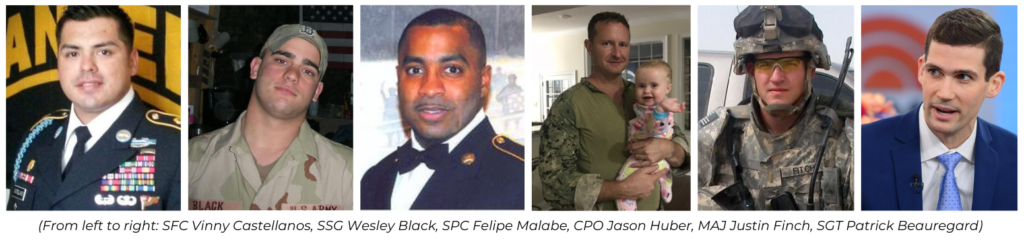

At least 64 post-9/11 service members and veterans that we know of have died from colorectal cancer. It has claimed the lives of many young service members and veterans: Army Ranger, SFC Vinny Castellanos at 36; Army Sniper, SSG Wesley Black at 36; Army Patient Assistant, SPC Felipe Malabe at 31; Navy SWCC and Rescue Swimmer, CPO Jason Huber at 35; Army Special Operations Enabler, MAJ Justin Finch at 33; and Marine Corps Intelligence Analyst, SGT Patrick Beauregard at 32. This is a small list of many who’ve died while in uniform or shortly after that. These men do not share many overlapping characteristics besides their young age and military service; a few hadn’t deployed.

UNIQUE EXPOSURES: BEYOND BURN PITS

CJ DePaulo’s bout with colon cancer left many wondering what the cause may have been. Through passive conversations, we continued to stumble across the Special Forces American military base in Arlit, Niger. Two of Africa’s most significant and highest-grade uranium mines lie within miles of the military base producing roughly 3,000 tons of uranium annually. Much of Arlit is littered with uranium mine cast downs that are resold to locals. Unfortunately, many of these items are radioactive. Over the years, hills of this debris have built up, containing potent radioactive substances such as radium, polonium, arsenic, and poisonous radon gasses. The open-air makes sure the particles are spread around the adjacent areas, and while the mine leadership states this limits its toxicity, this is far from the truth. Some of the surface roads in Arlit have measured over a hundred times standard radioactive values. Our team just completed an interview highlighting the airborne and inhalation-based toxins those airborne and inhalation-based toxins those who deploy face.

What about the others, like Felipe Malabe and Vinny Castellanos, who both deployed to South Korea in addition to Iraq, or Patrick Beauregard, who hadn’t deployed but was stationed at the Marine Intelligence School in Dam Neck, Virginia. Like Jason Huber, stationed at Dam Neck, Virginia, while in training and was then assigned to Special Boat Team-22 at the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Our team has seen alarming cancer trends in those who served at or within Virginia, Mississippi, and South Korea.

It doesn’t need to be a flaming pile of trash in a warzone to be considered toxic. More so, it is what the eyes don’t see. Men like those above, including CJ, did not have to die. Many cancers, especially colon cancer is treatable, and survivability is high if caught in the early stages. Understanding your potential exposures, speaking up when something isn’t right, and voicing those concerns (even if you need to push) with your care team is critical.

WHAT IS COLON CANCER?

Cancer is the result of uncontrolled cellular division. These cells are abnormal or damaged, and the proliferation and accumulation of these cells lead to tumor formation. These abnormal cells are a result of damage to our coding-DNA cells. Some individuals are born with predisposed mutations called “germline” mutations which can cause cancer later on in life – germline or inherited mutations account for approximately 5-10% of all cancers. The other 90% are considered “somatic,” meaning a mutation occurs after birth and happens sporadically or randomly – this is much of what we see in our military service members. More importantly, somatic mutations cannot be passed on from parents to children.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a disease of the colon or rectum, which are parts of the lower gastrointestinal (digestive) system. Unlike most cancers, CRC is often preventable with routine screening and highly treatable if detected early. While colon cancer can be hereditary (in those with Lynch Syndrome germline mutations), this is a rare occurrence, with just 1 in 5 colorectal cancer cases – we’ve yet to see a positive Lynch Syndrome-CRC case. It is most often diagnosed over age 65, with the average age at diagnosis being 68 years for men and 72 years for women.

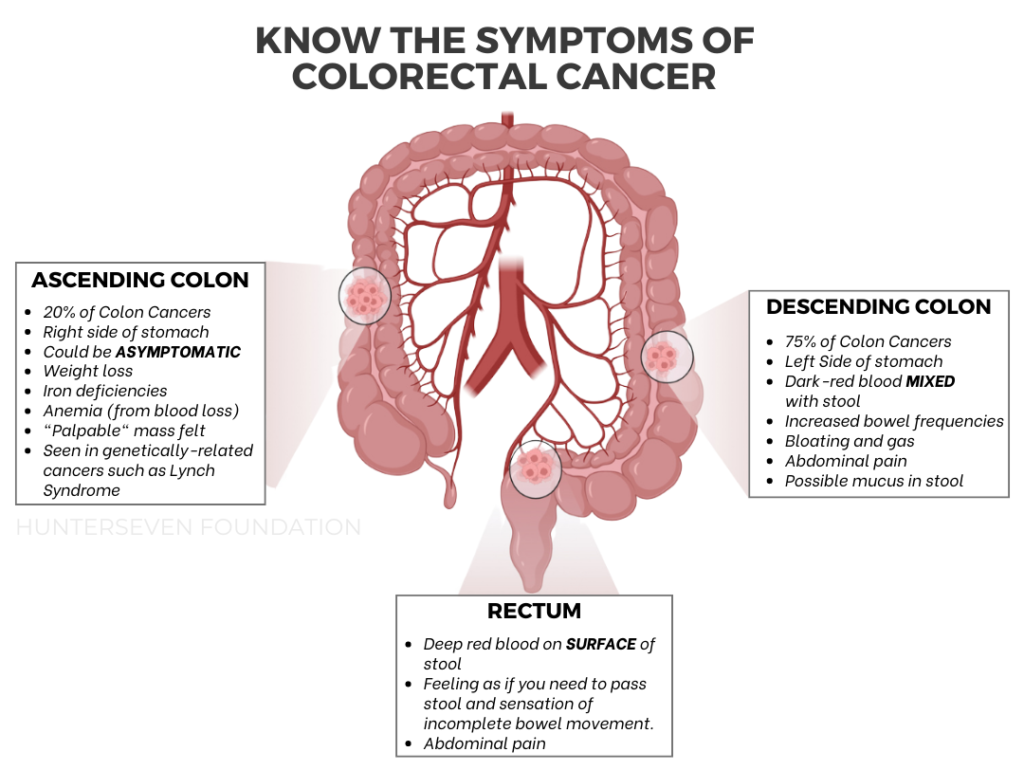

The gastrointestinal system is anatomically weird. The “small bowel” is stuffed in the middle of the stomach, and its purpose is to continue to break down food, absorb nutrients and move waste products into the colon (aka “large bowel”). The “large bowel” comprises the colon and rectum and is the target organ for this discussion. Understanding the gastro-geography broadly is because symptoms of colorectal cancer vary based on the location, as you’ll see below.

The ascending colon (right side of the abdomen) sees about 20% of all colon cancer cases. It is more common in those with a familial history / inherited germline mutation (i.e., Lynch Syndrome). This location is also more common in women and more challenging to treat, causing a worse prognosis. It is important to note that many right-sided colon cancers do not have obvious symptoms; often, patients are without symptoms (or asymptomatic). Interestingly, these right-sided colorectal cancers do not benefit from specific therapies (anti-EGFR) but seem to respond well to immunotherapies due to high antigenic loads. Another noted concern is the lack of diagnostic capabilities in testing, specifically fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), as it has been shown to provide inaccurate negative results in right-sided CRC patients in advanced stages of cancer.

The descending colon (left side of the abdomen) sees most colon cancers. Left-sided colon cancer often has symptoms that indicate something isn’t right, whether it be frequent bowel movements, pain, gas, or bloating. Because of the potential earlier onset of symptoms, this cancer may be identified earlier, leading to a better treatment outlook and a more vital prognosis. Cancers that occur on the left side benefit more from adjuvant chemotherapies. However, next-generation sequencing is highly recommended to ensure the treatments you are going through are adequate for your unique mutation – we recommend (and use) Guardant Healths liquid biopsy: Guardant360 for all of our solid tumor military/veteran patients followed by a CureMatch report to assure you are receiving an accurate, effective treatment.

WHAT CAUSES COLON CANCER?

Whenever we think about colon cancer, we often think about poor health, from an unhealthy diet to obesity, to drinking excessively and completely disregarding wellness. While that may be the case for the rest of the American population, the other one percent, our veteran military population, does not seem to fit that mold.

Until recently, diet and nutrition were deemed the most crucial external factor concerning cancer etiology and causation. Previously, the World Health Organization stated in 2003 that 70% of colon cancers could be prevented with appropriate dietary modifications. And additional activities and interventions could also help curb colon cancer risk, including physical activity and avoiding smoking and alcohol consumption. This is the recommendation for all cancers, though.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) suggests roughly 20% of colon cancers in males can be attributed to smoking and that individuals who consumed the highest rates of alcohol had a 60% greater risk of being diagnosed with colon cancer when compared to non- or light drinkers. So, looking at those two pieces of information, our post-9/11 military and veteran community is already at a seemingly increased risk… right? But what about the unique exposures we, as military veterans, face throughout service…

HELICOBACTER PYLORI:

If left untreated, H.pylori is a gastrointestinal bacterial infection that targets your stomach, increasing your risk for stomach (gastric) and colorectal cancers. H.pylori is one of the most common infections in the world, especially in developing countries. It is estimated that Iraq has an average of 70% infected population rate while nations in central Africa have an over rate while nations in central Africa are upwards of 90%. Since H.pylori isn’t a common concern in the United States, it is often overlooked as a potential risk factor. At the same time, related symptoms (such as acid reflux) can potentially be “masked” by antacids such as Prilosec, Zantac, or Protonix. H.pylori is easily identifiable through either a urea breath test (available to order and purchase on your own at Quest Health for $179 – or free if you can get your healthcare provider to call it) or a simple blood test similar to that of diabetic testing.

AMBIENT AIR POLLUTION:

Did you know that air pollution is a more significant threat to life expectancy than smoking worldwide? And some of the most highly polluted cities in the world coincide with the geographical locations we deploy to and are stationed at. Between 2018-2022, of the 131 ranked countries worldwide, we found eight of the usual areas for our cohort:

- #1 – Chad

- #2 – Iraq

- #3 – Pakistan

- #5 – Afghanistan

- #6 – Burkina Faso

- #7 – Kuwait

- #8 – Niger

- #14 – Qatar

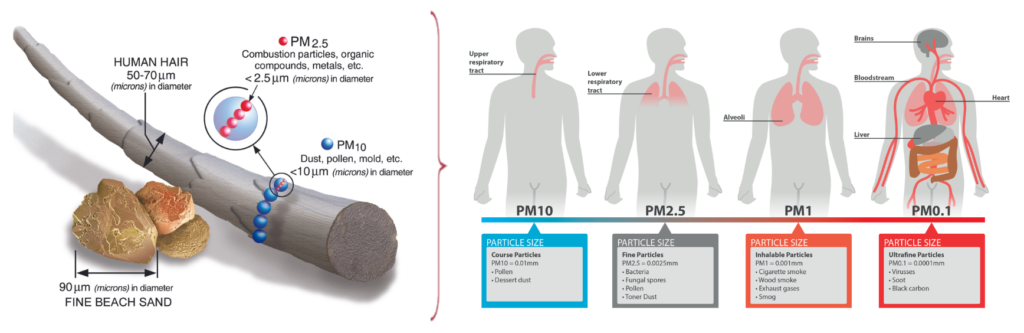

Of course, this is not an all-inclusive list, as some nations are so hostile it is challenging to evaluate. But it’s essential to note Chad and Niger are both two of the locations SFC CJ DePaulo deployed to. These nations have historically exceeded the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines by seven-to-ten times the safe exposure limits for particulate matter (PM) size 2.5 microns.

As shown in the image below, the average particulate size while deployed to the Middle East and Central Africa is between 2.5 microns and <1 micron in size. These exposures include exhaust fumes, soot, carbon from burn pits, and local pollution. Still, most importantly, these “man-made” exposures have the potential to collect and adhere to other chemicals, toxins, bacteria, and even viruses. When the particulate matter is 2.5 microns in size or less, it can travel deeper into the respiratory system. Because the lungs are the central hub for gas exchange, they require highly vascularized (blood supply), spongy tissues that can exchange oxygen-deficient blood cells through the capillary wall of the grape-like sacs called “alveoli” in lung bronchioles with oxygenated blood. Because of this process, toxins can quickly enter the bloodstream.

Not only are air pollution and micron-sized particulates dangerous for the lungs, but they are also a danger to the rest of your organ systems, as the lungs are the gatekeepers. Historically, we’ve seen many service members suffer from sudden cardiac arrest leading to death while overseas; majority have occurred following a physically taxing mission (such as that of Army Green Beret, SSG Jerry Gass) or after conducting outdoor exercises. We stress heavily on minimizing air pollution exposures whenever possible. Many of our cancer patients are sent a GrovPure Air Purification system. At the same time, they undergo chemotherapy and cancer treatments to decrease their risk of exposures. Still, we also push heavily for those forward deployed to take a look at personal protective gear like the Ventus Respiratory TR2.

URANIUM:

Uranium is the “chemical element of war.” While many would assume it is lead or something similar, it isn’t. Uranium has a 70% higher density than lead and has shown to be more effective in lethality but also protection when compared to lead. Each of us who has served in the military has been exposed to a form of Uranium (most often depleted Uranium) at some point. For those who have deployed to Arlit, Niger, like SFC CJ DePaulo – you have passively been exposed 99% of your time there.

Depleted Uranium (DU) is less radioactive (60% that of natural Uranium) and, in theory, should be safer concerning toxicity while maintaining its effectiveness in armor protection. It is assumed to be “weakly radioactive” only because of its long half-life duration (4 to 7 million years). Because of its weakness, the human body should excrete DU within 15 to 20 days – but this is a one-time exposure. Long-term (chronic) exposures have proven likely to negatively impact the gastrointestinal system, kidney function, liver function, brain, and blood-forming cells. One study that supports much of what we have seen in our Iraq War veterans is the correlation between Mosul, Iraq deployments, and the citizens – both with higher incidences of cancer with correlations to DU.

During the “Shock and Awe” component of the Invasion and the start of the Iraq War, over 130 tons of DU-munitions were fired by the United States and coalition forces (120mm and 30mm GAU-8/A). As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan progressed, so did the enemies’ weapons. The Global War on Terror became the “first” conflict to have a majority of combat-related deaths due to roadside bombs, improvised explosive devices (IED), and vehicle-borne IEDs. Because of its thickness over the lead, DU was embedded into the inner steel parts within armor and used in Abrams tanks, Bradley vehicles, Strykers, and Light-armored vehicles (LAVs). When a military vehicle takes fire or immobilizes from IED-like attacks, the DU would become “disrupted and airborne,” increasing the potential for inhalation and oral exposure.

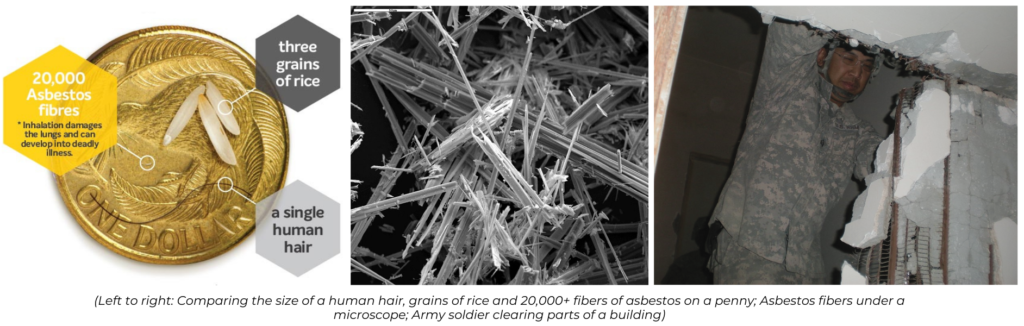

ASBESTOS

Asbestos is a group of naturally occurring minerals that were once widely used in construction, shipbuilding, and manufacturing due to their resistance to heat, fire, and chemicals. However, it was banned for new uses in the United States in 1989 due to its toxicity. When asbestos fibers are inhaled or ingested, they can become lodged in the lungs, digestive tract, or other body tissues and cause various health problems, including colon cancer.

Many buildings and structures damaged or destroyed during the Iraq War contained asbestos, putting the more than two million Americans who served during Operation Iraqi Freedom at risk of inhalation exposures and subsequent illnesses.

While the exact mechanism by which asbestos causes colorectal cancer is not fully understood, it is believed to involve chronic inflammation and oxidative stress (we covered how this causes cancer in a previous blog). Asbestos fibers are sharp and cause chronic irritation, inflammation, and scarring in the lining of the colon, which can lead to the development of abnormal cells and the formation of polyps or tumors over time. These particles can be inhaled (irritating lung tissue), absorbed (irritating skin cells), and ingested (irritating gastrointestinal tract). Additionally, asbestos fibers have been shown to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce DNA damage in colon cells, which can also contribute to cancer development. ROS are highly reactive molecules that can cause oxidative stress and damage cellular structures and DNA, leading to mutations that promote the growth and spread of cancerous cells.

Asbestos exposure increases the risk of several types of cancer, including lung cancer, mesothelioma, and colon cancer. Asbestos exposure should be avoided whenever possible, and individuals exposed to asbestos should undergo regular medical monitoring available at the Department of Veterans Affairs Environmental Health Coordinators to detect any potential health problems early on.

HOW DOES THE VETERAN POPULATION COMPARE TO THE AMERICAN POPULATION OVERALL?

While we have limited information from national cancer statistics in civilian and military populations, we can draw hypothesized, informed conclusions.

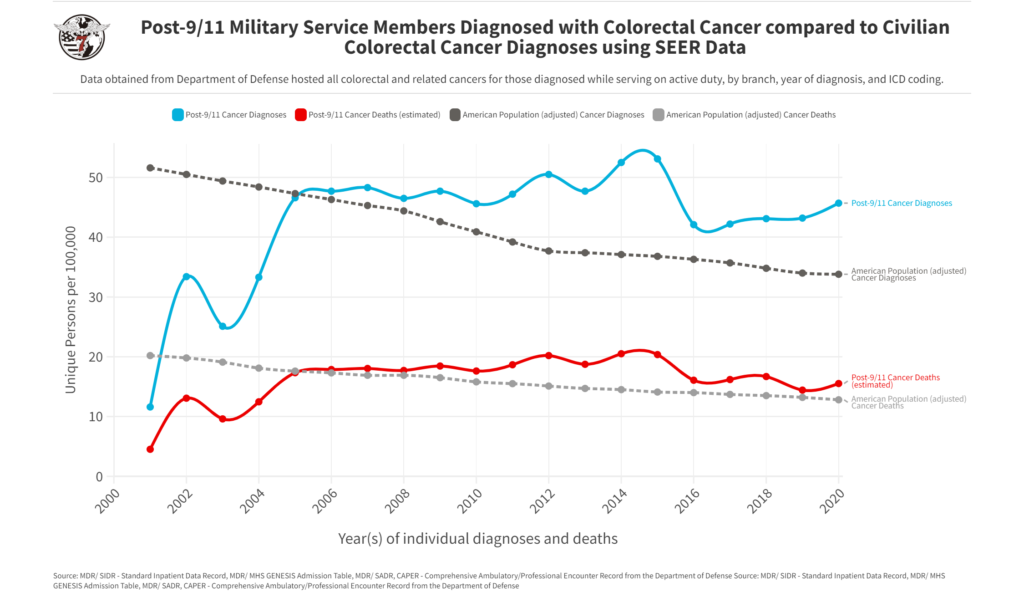

We utilized SEER colorectal cancer registry data (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). SEER is an American population-based cancer registry program that collects and publishes cancer incidence and survival data from various geographic regions and population groups in the United States. The program covers approximately 34.6% of the US population. This may seem like a small number, but this program is generally considered highly accurate and reliable as an overall predictor of cancer trends across America.

Below, the American population (control group) is annotated in gray with dotted lines. The data displays colon cancer diagnosed in the American people from 2001 to 2020. These numbers are displayed per 100,000.

The colored lines represent the number of active duty service members ONLY (veterans and reserves not included) diagnosed with colorectal cancer. The data has been displayed since the beginning of the Global War on Terror, 2001 to 2020, compared to that of the SEER-based civilian data. Each numeric is a unique patient, meaning this is not cumulative. The blue line represents the number of individual colorectal cancer diagnoses by year per 100,000 active duty post-9/11 service members. The red line represents the predictive death rate.

This data was directly accessed by the HunterSeven Foundation team with permission and direct access from the Department of Defense. These numbers only account for the active duty population. Once an individual leaves service, tracking cancer trends is arduous. Regardless, the data points are uncomfortable to review. The American population faces colon cancer between the ages of 68 and 72. Our active duty military population is much younger and faced increasing risk and rates as early as 2006. Be sure to keep up with routine screenings and note any changes in bowel movements or new onset symptoms. We’ve created a colon cancer fact sheet and our military exposures-specific CDC cancer screening guideline chart below.

Download: COLON CANCER FACT SHEET by HunterSeven Foundation

Download: Cancer-screening guidelines from CDC with Military Exposures risk